While naivete may have made me “brave” on occasion, flying is really all about experience. Between 1981 and 1988 through encounters with unexpected weather, difficult or unusual runways, tricky terrain, time pressure, leery passengers, and frequently a combination of these, I gained that experience. I learned about the capabilities of the plane, how to handle emergencies, my own fears and limits, and in the process became more confident of my own skills.

One dangerous phenomenon I never did become comfortable facing was icing. I first encountered icing in the spring of 1981. I had begun instrument flight training with Alan Evans, an instructor who was building up his time for his airline transport license. In April of that year, with winter almost over, Al suggested, “Why don’t we do a real IFR flight to Montreal? It’s the best way to learn.” He continued, “The weather at this time of year presents a unique opportunity. We won’t get thunderstorms yet and it’s no longer too cold. We can expect some cloud layers, but that should be fun. You can get some real cloud time.” That sounded like a wonderful idea.

We headed for Saint-Jean Airport on the outskirts of Montreal. The forecast called for overcast skies with cloud layers up to 12,000 feet and light to moderate icing in cloud in the upper levels. We decided to fly between layers and lower down. The first hour went fine. I got some excellent straight and level IFR time without the hood. (The IFR hood straps to the forehead and blocks the view outside the aircraft, allowing only the instrument panel to be seen. It trains pilots to fly by looking exclusively at the instruments, simulating flying in restricted or no visibility, as when flying in clouds.)

At 5,000 feet the cloud layers started to merge. Soon after entering cloud, I noticed a shiny translucent layer of ice on the wing struts and realized we were flying in icing conditions. Ice was gradually adhering to the strut surface. I had never experienced this before, but Al thankfully had. He understood my growing nervousness and advised “Concentrate on the flying. Leave the radio work to me.” But we continued to pick up more and more ice. Clearly uneasy now himself, Al requested a lower altitude of 4,000 feet hoping that the slightly higher temperature at that altitude would get us out of icing range. Technically, though, that altitude was inappropriate since a fundamental rule requires pilots to fly at odd thousand feet when going eastbound and even thousand westbound.

It was at least ten tense minutes before the center controller obliged and permitted us to descend. During this time our indicated airspeed had begun to drop even though the engine revolutions per minute (rpm) remained unchanged. With the same power, we were going slower. To avoid reaching stall speed, I progressively had to add more and more power until at one point I had the throttle all the way in. Even with full power, I only got 85 nautical miles per hour (knots) as opposed to a normal 100 knots. Here we were, 4,000 feet in the air, giving it all the power we had, and still the plane was slowing down.

I knew loss of power and even engine failure can occur when flying in clouds or precipitation at temperatures close to freezing because these conditions cause the carburetor intake to ice up in engines like mine. When the carburetor intake ices up, airflow into the engine is restricted, and when the engine does not receive adequate air it shuts down. To prevent such icing, I had the carburetor heat on constantly. Clearly, carburetor ice wasn’t the reason for our reduced speed: it was airframe icing.

I thought back on what I had learned. Accumulation of ice on the airframe can be a major weather hazard in aviation for many reasons. It destroys the lifting capability of the wing, increases drag which slows down the aircraft, and adds extra weight. As well, an iced-up propeller reduces thrust (forward motion). All of these factors render flight more difficult and in the worst circumstances can cause the aircraft to stall and/or become uncontrollable. More sophisticated aircraft, such as high-altitude airliners, are equipped with deicing equipment, but our little Cessna 172 did not come with that luxury.

We were obviously in quite some danger. Why wasn’t Al reacting, doing something, fast? I wanted to, but couldn’t; I wasn’t pilot-in-command. Trying to calm my worries, I reminded myself that Al was a highly experienced pilot, someone I could trust to gauge our situation more accurately than I could.

By now the ice on the struts and on the leading edges of the wings had grown to at least half an inch in thickness. Any moment now the plane could lose its lifting capability; our time was running out. Not only that. Our front windshield was covered by a solid sheet of ice. Forward visibility was zero. Here we were, flying at high speed with nothing but an opaque wall of white a few feet in front of our noses. It was claustrophobic, utterly disorienting. I couldn’t believe it. My skin began to tingle with a desperate need to scratch a hole in that ice. Visibility was no better to the side. Although those windows were ice free, all we could see was thick gray cloud. Meanwhile that layer of ice on the struts and wings was growing surely and steadily. I couldn’t take my eyes off it. When would it be too much? Worry escalated to panic. This was some IFR training; our lives were on the line.

Al suddenly interrupted, warning me to concentrate on the instruments. Those instructions thankfully broke the spell, brought me back to what I had to do, what I could deal with. Al asked Air Traffic Control (ATC) for permission to go even lower, to 3,000 feet. About five minutes later we were cleared to 3,000. Even that made not the slightest difference. Ice continued to accumulate. Worry again spiraled out of control. Why wasn’t Al requesting an immediate full descent clearance? We needed to get down, right down to the ground, and fast. That was our only salvation.

I began to grow suspicious. Was Al holding back longer than he should because he would have to admit flying into adverse and dangerous weather conditions instead of turning back? Was he afraid that such an error of judgment might prevent him from getting his airline transport rating? Or was I overreacting, beginning to panic uselessly because of my limited experience?

Minimum altitude restrictions exist when flying IFR and you need a good reason to break them. Well, we definitely had a good reason. Al could declare an emergency, which would force controllers to clear all traffic out of our way and give us first priority. Sure, Al would subsequently have to explain his actions and the reasons for the emergency, leading, potentially, to a thorough investigation by authorities. I knew that to avoid such repercussions pilots tend not to declare emergencies until they’re convinced beyond a shred of doubt they have no choice. Was this what was happening?

Suddenly rock-crunching sounds bombarded us. Massive vibrations shook the plane. I was stunned, terrified. Thoughts swirled. The propeller has cracked, pieces are breaking off causing the plane to fibrillate, the metal fuselage has ripped somewhere, something is tearing, breaking apart. My mind in free-fall, heart pounding with fear, I couldn’t grasp what was happening. It was good that Al was in control because I was momentarily beyond consciousness.

Al did finally get permission to come in for landing without declaring an emergency, and I landed us safely a short while later. Back on the ground, I could only marvel: all trace of ice had vanished. Al explained that the noise and vibrations were the result of ice melting and breaking off in chunks from the propeller and hurling against the plane. It was a terrifying experience that I never wanted to repeat. However, with temperatures in Canada frequently conducive to icing, it is unfortunately not always easy to avoid. Yet I vowed, if I ever found myself in such a situation again I would remain calm and ready to take corrective action.

One dangerous phenomenon I never did become comfortable facing was icing. I first encountered icing in the spring of 1981. I had begun instrument flight training with Alan Evans, an instructor who was building up his time for his airline transport license. In April of that year, with winter almost over, Al suggested, “Why don’t we do a real IFR flight to Montreal? It’s the best way to learn.” He continued, “The weather at this time of year presents a unique opportunity. We won’t get thunderstorms yet and it’s no longer too cold. We can expect some cloud layers, but that should be fun. You can get some real cloud time.” That sounded like a wonderful idea.

We headed for Saint-Jean Airport on the outskirts of Montreal. The forecast called for overcast skies with cloud layers up to 12,000 feet and light to moderate icing in cloud in the upper levels. We decided to fly between layers and lower down. The first hour went fine. I got some excellent straight and level IFR time without the hood. (The IFR hood straps to the forehead and blocks the view outside the aircraft, allowing only the instrument panel to be seen. It trains pilots to fly by looking exclusively at the instruments, simulating flying in restricted or no visibility, as when flying in clouds.)

At 5,000 feet the cloud layers started to merge. Soon after entering cloud, I noticed a shiny translucent layer of ice on the wing struts and realized we were flying in icing conditions. Ice was gradually adhering to the strut surface. I had never experienced this before, but Al thankfully had. He understood my growing nervousness and advised “Concentrate on the flying. Leave the radio work to me.” But we continued to pick up more and more ice. Clearly uneasy now himself, Al requested a lower altitude of 4,000 feet hoping that the slightly higher temperature at that altitude would get us out of icing range. Technically, though, that altitude was inappropriate since a fundamental rule requires pilots to fly at odd thousand feet when going eastbound and even thousand westbound.

It was at least ten tense minutes before the center controller obliged and permitted us to descend. During this time our indicated airspeed had begun to drop even though the engine revolutions per minute (rpm) remained unchanged. With the same power, we were going slower. To avoid reaching stall speed, I progressively had to add more and more power until at one point I had the throttle all the way in. Even with full power, I only got 85 nautical miles per hour (knots) as opposed to a normal 100 knots. Here we were, 4,000 feet in the air, giving it all the power we had, and still the plane was slowing down.

I knew loss of power and even engine failure can occur when flying in clouds or precipitation at temperatures close to freezing because these conditions cause the carburetor intake to ice up in engines like mine. When the carburetor intake ices up, airflow into the engine is restricted, and when the engine does not receive adequate air it shuts down. To prevent such icing, I had the carburetor heat on constantly. Clearly, carburetor ice wasn’t the reason for our reduced speed: it was airframe icing.

I thought back on what I had learned. Accumulation of ice on the airframe can be a major weather hazard in aviation for many reasons. It destroys the lifting capability of the wing, increases drag which slows down the aircraft, and adds extra weight. As well, an iced-up propeller reduces thrust (forward motion). All of these factors render flight more difficult and in the worst circumstances can cause the aircraft to stall and/or become uncontrollable. More sophisticated aircraft, such as high-altitude airliners, are equipped with deicing equipment, but our little Cessna 172 did not come with that luxury.

We were obviously in quite some danger. Why wasn’t Al reacting, doing something, fast? I wanted to, but couldn’t; I wasn’t pilot-in-command. Trying to calm my worries, I reminded myself that Al was a highly experienced pilot, someone I could trust to gauge our situation more accurately than I could.

By now the ice on the struts and on the leading edges of the wings had grown to at least half an inch in thickness. Any moment now the plane could lose its lifting capability; our time was running out. Not only that. Our front windshield was covered by a solid sheet of ice. Forward visibility was zero. Here we were, flying at high speed with nothing but an opaque wall of white a few feet in front of our noses. It was claustrophobic, utterly disorienting. I couldn’t believe it. My skin began to tingle with a desperate need to scratch a hole in that ice. Visibility was no better to the side. Although those windows were ice free, all we could see was thick gray cloud. Meanwhile that layer of ice on the struts and wings was growing surely and steadily. I couldn’t take my eyes off it. When would it be too much? Worry escalated to panic. This was some IFR training; our lives were on the line.

Al suddenly interrupted, warning me to concentrate on the instruments. Those instructions thankfully broke the spell, brought me back to what I had to do, what I could deal with. Al asked Air Traffic Control (ATC) for permission to go even lower, to 3,000 feet. About five minutes later we were cleared to 3,000. Even that made not the slightest difference. Ice continued to accumulate. Worry again spiraled out of control. Why wasn’t Al requesting an immediate full descent clearance? We needed to get down, right down to the ground, and fast. That was our only salvation.

I began to grow suspicious. Was Al holding back longer than he should because he would have to admit flying into adverse and dangerous weather conditions instead of turning back? Was he afraid that such an error of judgment might prevent him from getting his airline transport rating? Or was I overreacting, beginning to panic uselessly because of my limited experience?

Minimum altitude restrictions exist when flying IFR and you need a good reason to break them. Well, we definitely had a good reason. Al could declare an emergency, which would force controllers to clear all traffic out of our way and give us first priority. Sure, Al would subsequently have to explain his actions and the reasons for the emergency, leading, potentially, to a thorough investigation by authorities. I knew that to avoid such repercussions pilots tend not to declare emergencies until they’re convinced beyond a shred of doubt they have no choice. Was this what was happening?

Suddenly rock-crunching sounds bombarded us. Massive vibrations shook the plane. I was stunned, terrified. Thoughts swirled. The propeller has cracked, pieces are breaking off causing the plane to fibrillate, the metal fuselage has ripped somewhere, something is tearing, breaking apart. My mind in free-fall, heart pounding with fear, I couldn’t grasp what was happening. It was good that Al was in control because I was momentarily beyond consciousness.

Al did finally get permission to come in for landing without declaring an emergency, and I landed us safely a short while later. Back on the ground, I could only marvel: all trace of ice had vanished. Al explained that the noise and vibrations were the result of ice melting and breaking off in chunks from the propeller and hurling against the plane. It was a terrifying experience that I never wanted to repeat. However, with temperatures in Canada frequently conducive to icing, it is unfortunately not always easy to avoid. Yet I vowed, if I ever found myself in such a situation again I would remain calm and ready to take corrective action.

Icing is only one of the risks you face when flying in Canada. A flight in 1987 in the dead of winter with temperatures down to -20º C brought me head to head with other unexpected problems.

Ulrike and I had decided to fly across Canada to Edmonton, Alberta, for a very special Baltic-German Christmas celebration with Ulrike’s large family, up to 18 people most of the time. Our children were coming, too. By now we had a second daughter, Anita, who was six, and a son, Julian, two. They were accompanying us in the Cessna; Tara, almost 15, had school exams and would arrive a little later by commercial plane. We were thrilled at the thought of flying that distance in winter. It actually made sense to us at the time, taking a treacherous flight in a little Cessna with small children.

Christmas in Ulrike’s family was celebrated on Christmas Eve. It followed the Lutheran traditions customary in the family’s original homeland Latvia. The family, like all Baltic Germans, had been forced to leave Latvia in 1939. Ulrike in fact was born in Poland while it was under German occupation toward the end of the Second World War. Her father, Dr. Gerhard Conradi, emigrated with the family to Canada in 1952, landing finally in Edmonton where he became a well-known and beloved pediatrician.

Edmonton, a mid-sized prairie city that straddles the North Saskatchewan River in central Alberta - “a sunny place, a good reason to stay,” my mother-in-law Karin always said - became the family’s permanent home. Of their five children, three remained and raised their families there, and so a visit always meant a lot of catching up. In fact, after meeting Ulrike, I’d taken a German course, a big plus not just on our honeymoon, but on occasions such as Christmas, because German was still spoken at home.

Ulrike and I had decided to fly across Canada to Edmonton, Alberta, for a very special Baltic-German Christmas celebration with Ulrike’s large family, up to 18 people most of the time. Our children were coming, too. By now we had a second daughter, Anita, who was six, and a son, Julian, two. They were accompanying us in the Cessna; Tara, almost 15, had school exams and would arrive a little later by commercial plane. We were thrilled at the thought of flying that distance in winter. It actually made sense to us at the time, taking a treacherous flight in a little Cessna with small children.

Christmas in Ulrike’s family was celebrated on Christmas Eve. It followed the Lutheran traditions customary in the family’s original homeland Latvia. The family, like all Baltic Germans, had been forced to leave Latvia in 1939. Ulrike in fact was born in Poland while it was under German occupation toward the end of the Second World War. Her father, Dr. Gerhard Conradi, emigrated with the family to Canada in 1952, landing finally in Edmonton where he became a well-known and beloved pediatrician.

Edmonton, a mid-sized prairie city that straddles the North Saskatchewan River in central Alberta - “a sunny place, a good reason to stay,” my mother-in-law Karin always said - became the family’s permanent home. Of their five children, three remained and raised their families there, and so a visit always meant a lot of catching up. In fact, after meeting Ulrike, I’d taken a German course, a big plus not just on our honeymoon, but on occasions such as Christmas, because German was still spoken at home.

Christmas in Edmonton was rare for us and always special, and this time even more so because we would be flying there in the Cessna. Time, unfortunately, was limited since we had to be back in Toronto for work and school at the start of the New Year. The flight was long. I estimated at least nineteen hours of flying. Daylight hours at this time of year were short. We hoped to put in five to six hours of flying a day, which would get us there in three to four days, weather permitting and barring unforeseen problems. Naive optimists that we were, we did not expect any.

We were excited about the trip, and I prepared well. The evening before our scheduled departure date, I drove down to the main weather office at Toronto International to get a personalized weather briefing. The next day would be fine as long as we took the route south of Lake Superior through the States and then continued up toward Winnipeg, Manitoba. Cloud tops were forecasted for around 5,000 feet; temperatures would be colder than -15ºC, too cold for icing conditions in clouds.

We lifted off shortly after eight into a gray overcast, which always left me feeling uneasy in cold weather after my icing experience. With my eyes glued to the instruments, we climbed through the stuff as it gradually thinned out and grew wispier until, wham, we emerged into blue skies, fluffy cotton-ball clouds rapidly falling away below us. Ulrike and I looked around for our sunglasses.

It was a smooth flight to the Canadian Soo (Sault Ste. Marie). A quick update with the FSS (Flight Service Station) over the phone confirmed the weather would continue to be clear, but we ought to keep an eye on headwinds that could pick up as we traversed west. Since we did not have any GPS or DME (Distance Measuring Equipment) on board, I had to use VOR radials (Very high frequency Omni direction Range) to calculate our ground speed, a popular time-tested navigational system still in use. Sure enough, during a smooth flight into the approaching dusk, at 7,000 feet, our ground speed was no more than 85 knots versus a true airspeed of 105, indicating a reasonably stiff headwind.

By the time we got close to the south shore of Lake Superior at Ashland, about 70 miles from our destination of Duluth, Minnesota, night had fallen. On checking the fuel gauges I noticed that both were showing only about one-eighth full even though by my calculations I should have had at least 1.5 hours of fuel remaining, just under a quarter tank. I began to feel tense. Wanting to shorten the distance, I decided to scrap flying along the shoreline and to cut across the corner of the lake instead.

After a while it struck me. What was I doing? With fuel looking really low, I was flying in the dark in icy weather over a frozen lake. Duluth, just a line of blinking lights up ahead. It seemed close, but was it maybe just that tiny stretch between life and death not close enough? How could I have put us in this situation? Ulrike was sitting tight and quiet next to me, focusing as if by sheer force of will she could make that distance shrink. Unspoken between us hovered the frightening question: Was the ice below thick enough to support us if we had to make an emergency landing? Or would it break, a big black hole in all that white the only indicator of where we had been?

I swallowed hard, stared at the lights ahead, back at the shore receding behind us, at the lights again. They hardly seemed closer. We were barely moving in the strong headwinds. My calculations said we were ok, but those fuel gauges indicated otherwise. I promised myself, if we made it through, never again would I try something so stupid! Interminable minutes later, I was finally able to contact Duluth Approach Control - how sweet that deep voice - and request my descent. I blew Ulrike a kiss. We would make it.

After landing I checked the fuel. There was plenty left; my calculations had been correct. Those fuel gauges, simplistic instruments that use a needle to mark fuel quantity, had been misleading. How needlessly they had frightened us. Yet even knowing how imprecise they are, when that needle hovers over E, anxiety builds.

We actually got into Duluth just in the nick of time because early the next day about a foot of snow descended on the city, not unusual for this neck of the woods at the edge of the Great Lakes at that time of year. We made the best of it and walked into town, which was festive with pre-Christmas preparations. The kids had sleigh rides and conferred with Santa. In the evening all of us cozied up to a wood fireplace back in our hotel room.

We were excited about the trip, and I prepared well. The evening before our scheduled departure date, I drove down to the main weather office at Toronto International to get a personalized weather briefing. The next day would be fine as long as we took the route south of Lake Superior through the States and then continued up toward Winnipeg, Manitoba. Cloud tops were forecasted for around 5,000 feet; temperatures would be colder than -15ºC, too cold for icing conditions in clouds.

We lifted off shortly after eight into a gray overcast, which always left me feeling uneasy in cold weather after my icing experience. With my eyes glued to the instruments, we climbed through the stuff as it gradually thinned out and grew wispier until, wham, we emerged into blue skies, fluffy cotton-ball clouds rapidly falling away below us. Ulrike and I looked around for our sunglasses.

It was a smooth flight to the Canadian Soo (Sault Ste. Marie). A quick update with the FSS (Flight Service Station) over the phone confirmed the weather would continue to be clear, but we ought to keep an eye on headwinds that could pick up as we traversed west. Since we did not have any GPS or DME (Distance Measuring Equipment) on board, I had to use VOR radials (Very high frequency Omni direction Range) to calculate our ground speed, a popular time-tested navigational system still in use. Sure enough, during a smooth flight into the approaching dusk, at 7,000 feet, our ground speed was no more than 85 knots versus a true airspeed of 105, indicating a reasonably stiff headwind.

By the time we got close to the south shore of Lake Superior at Ashland, about 70 miles from our destination of Duluth, Minnesota, night had fallen. On checking the fuel gauges I noticed that both were showing only about one-eighth full even though by my calculations I should have had at least 1.5 hours of fuel remaining, just under a quarter tank. I began to feel tense. Wanting to shorten the distance, I decided to scrap flying along the shoreline and to cut across the corner of the lake instead.

After a while it struck me. What was I doing? With fuel looking really low, I was flying in the dark in icy weather over a frozen lake. Duluth, just a line of blinking lights up ahead. It seemed close, but was it maybe just that tiny stretch between life and death not close enough? How could I have put us in this situation? Ulrike was sitting tight and quiet next to me, focusing as if by sheer force of will she could make that distance shrink. Unspoken between us hovered the frightening question: Was the ice below thick enough to support us if we had to make an emergency landing? Or would it break, a big black hole in all that white the only indicator of where we had been?

I swallowed hard, stared at the lights ahead, back at the shore receding behind us, at the lights again. They hardly seemed closer. We were barely moving in the strong headwinds. My calculations said we were ok, but those fuel gauges indicated otherwise. I promised myself, if we made it through, never again would I try something so stupid! Interminable minutes later, I was finally able to contact Duluth Approach Control - how sweet that deep voice - and request my descent. I blew Ulrike a kiss. We would make it.

After landing I checked the fuel. There was plenty left; my calculations had been correct. Those fuel gauges, simplistic instruments that use a needle to mark fuel quantity, had been misleading. How needlessly they had frightened us. Yet even knowing how imprecise they are, when that needle hovers over E, anxiety builds.

We actually got into Duluth just in the nick of time because early the next day about a foot of snow descended on the city, not unusual for this neck of the woods at the edge of the Great Lakes at that time of year. We made the best of it and walked into town, which was festive with pre-Christmas preparations. The kids had sleigh rides and conferred with Santa. In the evening all of us cozied up to a wood fireplace back in our hotel room.

We departed for Winnipeg the day after. Approaching the Lake of the Woods area, we flew over countless frozen lakes, their wind-blown snow patterns as endlessly varied as snowflakes; a total delight. The weather was mostly cloudy. Scattered snow flurries made me wonder about landing conditions at Winnipeg.

On the Winnipeg ATIS (Automatic Terminal Information Service) I heard that there was snow on the runway and that the James Brake Index was 0.8. This index is an indicator of expected braking effectiveness. 0.8 was not bad and would not pose a problem for a Cessna 172. Ironically, after landing safely, as I stepped out of the aircraft, I slipped and fell on a patch of ice.

After refueling and buying sandwiches, drinks and coffee, we departed for Regina, Saskatchewan, just under 300 miles away. At Regina, the outside temperature was a frigid -22ºC. After touching down and securing the plane for the night, we could hardly wait for a long soak in the hotel hot tub. Flying with the children was actually great fun and really easy. The steady drone of the engine put our little Anita fast asleep within minutes of takeoff, and Julian had building blocks to keep him busy.

The next morning at the airport it was even colder, -24ºC. I asked Ulrike to stay inside the terminal with the kids while I started and warmed up the aircraft. I followed my cold weather start-up check list. The engine sprang to life instantly, but, not being familiar with such extreme cold weather conditions, I didn’t wait long enough during my ground run-up to warm everything up sufficiently. When I pulled the carburetor heat knob out as part of my preflight checks, the carburetor cable snapped like an icicle and a whole foot and a half came out in my hand. As Ulrike approached the plane with Julian all bundled up in her arms and Anita running behind her, ready to climb aboard, I told her what had happened. We were dismayed because the repair could mean a lengthy delay if there was no one around who could fix it right away. How silly. Because of this one stupid error we could end up missing the Christmas festivities.

At the repairs hangar a few hundred yards away, we got a pre-Christmas present. The chief engineer, a tall, strapping African from Eritrea, was there and ready to help, offering to pull us into the hangar and deal with the carburetor heat cable right away. This was a very kind gesture for a minor job given that opening the huge hangar doors would mean a tremendous loss of heat.

As his mechanic got to work and Ulrike and the kids relaxed in the office, he offered me a coffee. He asked where I was from, and as I went over my background, he told me full of enthusiasm, “In Eritrea we would see all the Hindi movies from India; Indian women are so beautiful! Why did you not marry one of those beauties?” Ulrike laughed on hearing that he had not considered her the right wife for me. In under an hour, while we chatted, the plane was repaired, and we were on our way to Edmonton City Centre Airport. In less than four hours, on Christmas Eve, we landed in sunny Edmonton with the outside temperature a balmy -5ºC.

On the Winnipeg ATIS (Automatic Terminal Information Service) I heard that there was snow on the runway and that the James Brake Index was 0.8. This index is an indicator of expected braking effectiveness. 0.8 was not bad and would not pose a problem for a Cessna 172. Ironically, after landing safely, as I stepped out of the aircraft, I slipped and fell on a patch of ice.

After refueling and buying sandwiches, drinks and coffee, we departed for Regina, Saskatchewan, just under 300 miles away. At Regina, the outside temperature was a frigid -22ºC. After touching down and securing the plane for the night, we could hardly wait for a long soak in the hotel hot tub. Flying with the children was actually great fun and really easy. The steady drone of the engine put our little Anita fast asleep within minutes of takeoff, and Julian had building blocks to keep him busy.

The next morning at the airport it was even colder, -24ºC. I asked Ulrike to stay inside the terminal with the kids while I started and warmed up the aircraft. I followed my cold weather start-up check list. The engine sprang to life instantly, but, not being familiar with such extreme cold weather conditions, I didn’t wait long enough during my ground run-up to warm everything up sufficiently. When I pulled the carburetor heat knob out as part of my preflight checks, the carburetor cable snapped like an icicle and a whole foot and a half came out in my hand. As Ulrike approached the plane with Julian all bundled up in her arms and Anita running behind her, ready to climb aboard, I told her what had happened. We were dismayed because the repair could mean a lengthy delay if there was no one around who could fix it right away. How silly. Because of this one stupid error we could end up missing the Christmas festivities.

At the repairs hangar a few hundred yards away, we got a pre-Christmas present. The chief engineer, a tall, strapping African from Eritrea, was there and ready to help, offering to pull us into the hangar and deal with the carburetor heat cable right away. This was a very kind gesture for a minor job given that opening the huge hangar doors would mean a tremendous loss of heat.

As his mechanic got to work and Ulrike and the kids relaxed in the office, he offered me a coffee. He asked where I was from, and as I went over my background, he told me full of enthusiasm, “In Eritrea we would see all the Hindi movies from India; Indian women are so beautiful! Why did you not marry one of those beauties?” Ulrike laughed on hearing that he had not considered her the right wife for me. In under an hour, while we chatted, the plane was repaired, and we were on our way to Edmonton City Centre Airport. In less than four hours, on Christmas Eve, we landed in sunny Edmonton with the outside temperature a balmy -5ºC.

In no time at all we were at the Conradi family home and the big front doors opened, greetings and laughter engulfing us as welcoming hands grabbed our suitcases and hung up our coats. We were just in time. Everyone, including Tara, was already there ready for the celebration.

Christmas Eve began with a good swig of vodka. And since you never drink vodka on its own, we alternated each swig with bites of tiny Speckkuchen (bacon, onion and currant turnover) or some other fat-rich delicacy to soften the effects of the alcohol. We repeated this zakuska - a Russian, and Baltic, tradition - several times, helping to loosen my tongue and add Prost and Na Zdorovye to my vocabulary. Next came a cold buffet with rossolj (a delicious Russian salad made of red beets, matjes herring and potatoes), smoked fish and eel, smoked duck breast, and crusty breads of various kinds.

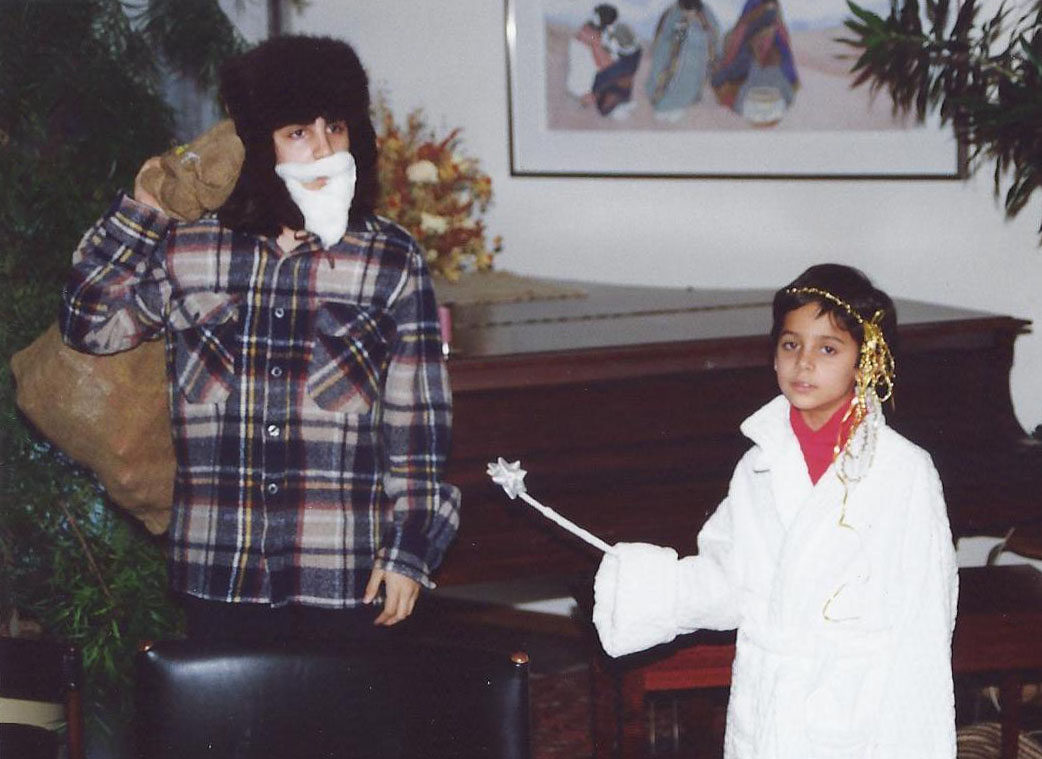

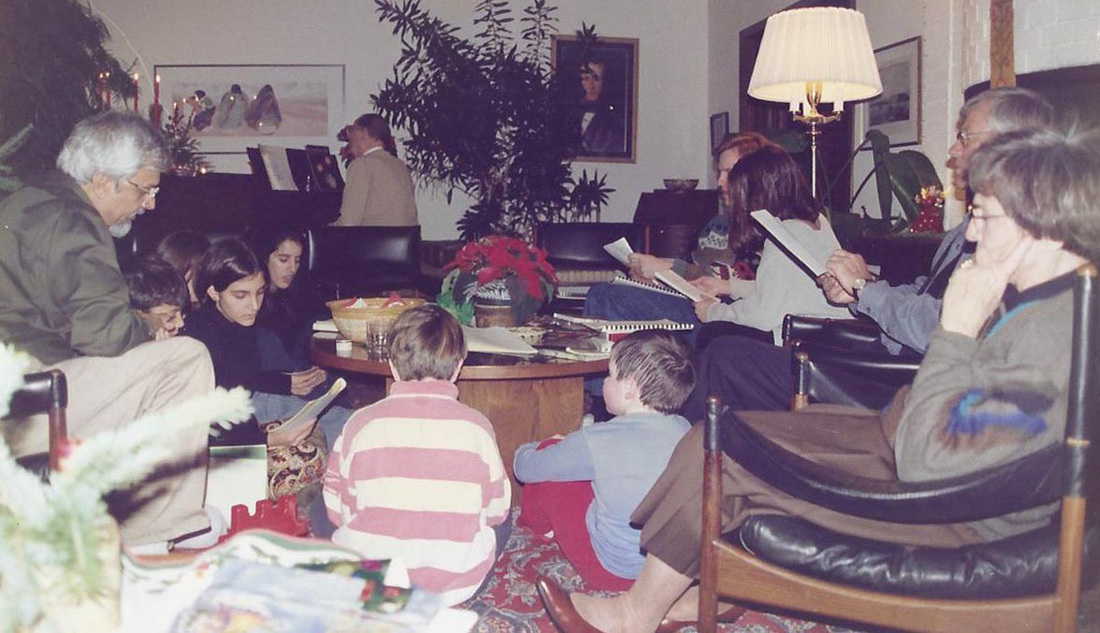

Later in the evening Ulrike’s father carefully opened the large, centuries-old, leather-bound family Bible and read a passage about Christ’s birth as candles, giving off a pleasant smell of wax, burned on the large pine Christmas tree, a pail of water at the ready for any emergency. Afterwards he sat at the Steinway baby grand and, smiling, played old beloved German Christmas songs, improvising the accompaniment. Singers crowded around, craning their necks to read the words on the sheet music, the rest of us humming happily along. Children then nervously recited poems that had taken weeks to learn in German, or they performed Christmas skits, adjusting a loose wing here or a slipping halo there. One or two played a piece on the piano or violin or cello, whatever instrument they were learning at the time.

Christmas Eve began with a good swig of vodka. And since you never drink vodka on its own, we alternated each swig with bites of tiny Speckkuchen (bacon, onion and currant turnover) or some other fat-rich delicacy to soften the effects of the alcohol. We repeated this zakuska - a Russian, and Baltic, tradition - several times, helping to loosen my tongue and add Prost and Na Zdorovye to my vocabulary. Next came a cold buffet with rossolj (a delicious Russian salad made of red beets, matjes herring and potatoes), smoked fish and eel, smoked duck breast, and crusty breads of various kinds.

Later in the evening Ulrike’s father carefully opened the large, centuries-old, leather-bound family Bible and read a passage about Christ’s birth as candles, giving off a pleasant smell of wax, burned on the large pine Christmas tree, a pail of water at the ready for any emergency. Afterwards he sat at the Steinway baby grand and, smiling, played old beloved German Christmas songs, improvising the accompaniment. Singers crowded around, craning their necks to read the words on the sheet music, the rest of us humming happily along. Children then nervously recited poems that had taken weeks to learn in German, or they performed Christmas skits, adjusting a loose wing here or a slipping halo there. One or two played a piece on the piano or violin or cello, whatever instrument they were learning at the time.

All the while we nibbled goodies piled high on Christmas plates. There were Pfefferkuchen (a type of gingerbread), usually in star, heart, and crescent-moon shapes, Pumpernickel (not your familiar dark bread, but a hazelnut concoction) Sandplaetzchen full of butter, icing sugar and flour, and many other kinds of cookies baked months in advance by my mother-in-law. There were marzipan apples and pears, and slices of the famous Niederegger chocolate-covered marzipan bars, and mandarin oranges and nuts.

A tall St. Nick would come in through the French doors dragging a bulky bag. After he left it was time to open presents, a long slow process because each present had to be seen and touched, passed around and admired by everyone. As the candles burned down and Christmas carols or Handel’s Messiah played on the record player, everyone gradually grew quiet, sank deeper into a cozy chair, engrossed in a new book or toy while the evening drew to a close. But, this was only the beginning. We all looked forward to the next day’s family feast in which we would all thoroughly overindulge.

All too soon, these most enjoyable days were over and I had to think about flying back to Toronto. I hoped to arrive there December 30. This time Tara and Anita were coming back with me, and Ulrike and Julian would return later by commercial aircraft after spending an extra week with the family.

While in Edmonton, to protect the plane and especially to make absolutely sure there would be no possibility of parts breaking due to insufficient heating, I had parked the airplane inside a heated hangar. This way, when I finally started her up, she would be in good running condition and would have no cold-weather issues. On the day of departure, though, as I was doing the run-up, I sensed some engine roughness. Strange. The cold couldn’t have anything to do with it. Perhaps the magneto, the ignition system, was to blame, or maybe something connected with the fuel system, or moisture in the tank from being in the hangar. A couple of minutes later, however, during my run up checks, the engine roughness was gone. Whatever it was seemed to have corrected itself.

I continued with my preparations, got my IFR clearance to Saskatoon and taxied to the active runway. On the roll out, with full power, she once again did not respond in the usual way - there was a noticeable hesitation. I started to climb, keeping an eye on the gauges, ears alert, wondering if things would settle. But they didn’t and on reaching 1,000 feet above ground, I reported the engine roughness and requested a return. By the time I was on the base leg and ready to land, however, I again felt everything had come back to normal. Should I land now or continue? I opted to continue. I did not feel one hundred per cent at ease, but let it slide, something I had been taught never to do.

The rest of the flight to Saskatoon was uneventful. After refueling and getting a bite to eat, we got a clearance to Winnipeg and departed in the early afternoon. The cockpit was colder than normal. I gazed at the outside air temperature gauge, which showed -28ºC at 9,000 feet. Tara was asleep in the front with me, looking cold with her hat, scarf and mitts on. Anita, unusually for her, was awake in the back and gazing out of the window at the ground below. It was nearing dusk and stars were becoming visible in the crisp, Prairie sky.

By the time we passed Yorkton, it was fully dark outside. Suddenly I noticed something strange. The attitude indicator, which is a gauge that shows a miniature plane and its relation to an artificial horizon, had the little plane leaning as if in a left turn. I didn’t think I was turning. I looked outside to check. In the clear night, with the ground visible due to the snow and the towns twinkling brightly, I could see the horizon perfectly and saw that I was flying level. Obviously, the attitude indicator was malfunctioning.

To determine the cause of the problem, I made a rate one turn to the right for a few seconds followed by another to the left. The directional gyro was not responding either. This confirmed it: the vacuum pump had failed. A vacuum pump failure renders these two key navigation instruments useless. Thankfully, it does not in any way compromise the working of the engine.

I immediately informed the Winnipeg controller that I had suffered a vacuum pump failure, asking at the same time to be cleared down to 7,000 feet. He obliged. As I began my descent I thought, Why did I do that? She’s flying fine, the visibility, radio reception and gliding range are obviously better from higher up, and there are backup navigation instruments on board to help. I suppose, feeling vulnerable and rattled, I had instinctively wanted to be closer to the ground. Ah! That’s what my instructor had stressed in instrument ground school. He had warned us that in an emergency most pilots act instinctively and without thought, considering some action better than no action. On realizing a moment later the foolishness of reducing altitude, I requested a return to 9,000. The engine continued to do a fine job, immune to the navigation equipment failure.

As my heart rate returned to normal, I explained what had happened to Tara and asked her to help Anita retrieve my flight bag from the luggage hold behind her. I asked her to pull out the soap-holder suction cups that I had purchased for just such eventualities, as advised by IFR instructors. These fit nicely over the instrument gauges. I used them to cover up the attitude and direction indicators to prevent distraction by dysfunctional instruments. Center wanted to know our progress and whether any assistance was required. I informed them that all was fine now but that I would land earlier, in Brandon, Manitoba, about 100 miles west of Winnipeg.

A fire engine waited to greet us as we were pulling up to the terminal, a routine response in situations like ours. Luckily the plane didn’t need the fire engine, but we ourselves did because the airport by that time was totally deserted. We hitched a ride into town with it, the fire chief graciously taking us to the nearest hotel. After all this excitement we were glad to be able to go and relax in a hot tub, but not before I phoned in a report to Ulrike in Edmonton.

At 08:00 next day, New Year’s Eve, we arrived back at the Brandon terminal building with our fingers crossed. We knew it was highly unlikely an engineer would still be around on New Year’s Eve, and even more that he would be able to help with the vacuum pump. But, unbelievably, we had success on both fronts and would soon be able to continue the flight. I left Tara and Anita at the plane with the engineer and walked over to the briefing office to get the weather and to file a flight plan. Twenty minutes later, while I was in the midst of filling in the flight plan form, Anita ran up, agitated, and blurted out, “Papa, the engineer said to tell you that you’re not going anywhere today!”

We rushed back to the hangar where the engineer informed me, “You have a bent push-rod in one cylinder.” He had noticed it while changing the vacuum pump. A bent push-rod? This was serious and could lead to engine failure. Offhand he couldn’t offer any explanation as to the possible cause but seemed to feel that the roughness I’d experienced on leaving Edmonton may have something to do with it. Only an internal examination could confirm that. But why did the vacuum pump fail? Was there a connection or was it simply coincidence? No one knew. I could only thank my lucky stars, or Trevor’s horseshoe perhaps, that the vacuum pump failed when it did. It made me land earlier and possibly saved us from a real and potentially disastrous emergency.

I now arranged for the mechanics to fix the aircraft as soon as possible and then rushed out to see if we could fly commercially to Toronto. Luck was again on our side. There was a scheduled Canadian Pacific flight for Toronto right out of Brandon in three hours, and they had seats for us. While we didn’t arrive back in Toronto on December 30, as originally planned, we did make it back a half hour before midnight, New Year’s Eve, in time for a party with friends.

A tall St. Nick would come in through the French doors dragging a bulky bag. After he left it was time to open presents, a long slow process because each present had to be seen and touched, passed around and admired by everyone. As the candles burned down and Christmas carols or Handel’s Messiah played on the record player, everyone gradually grew quiet, sank deeper into a cozy chair, engrossed in a new book or toy while the evening drew to a close. But, this was only the beginning. We all looked forward to the next day’s family feast in which we would all thoroughly overindulge.

All too soon, these most enjoyable days were over and I had to think about flying back to Toronto. I hoped to arrive there December 30. This time Tara and Anita were coming back with me, and Ulrike and Julian would return later by commercial aircraft after spending an extra week with the family.

While in Edmonton, to protect the plane and especially to make absolutely sure there would be no possibility of parts breaking due to insufficient heating, I had parked the airplane inside a heated hangar. This way, when I finally started her up, she would be in good running condition and would have no cold-weather issues. On the day of departure, though, as I was doing the run-up, I sensed some engine roughness. Strange. The cold couldn’t have anything to do with it. Perhaps the magneto, the ignition system, was to blame, or maybe something connected with the fuel system, or moisture in the tank from being in the hangar. A couple of minutes later, however, during my run up checks, the engine roughness was gone. Whatever it was seemed to have corrected itself.

I continued with my preparations, got my IFR clearance to Saskatoon and taxied to the active runway. On the roll out, with full power, she once again did not respond in the usual way - there was a noticeable hesitation. I started to climb, keeping an eye on the gauges, ears alert, wondering if things would settle. But they didn’t and on reaching 1,000 feet above ground, I reported the engine roughness and requested a return. By the time I was on the base leg and ready to land, however, I again felt everything had come back to normal. Should I land now or continue? I opted to continue. I did not feel one hundred per cent at ease, but let it slide, something I had been taught never to do.

The rest of the flight to Saskatoon was uneventful. After refueling and getting a bite to eat, we got a clearance to Winnipeg and departed in the early afternoon. The cockpit was colder than normal. I gazed at the outside air temperature gauge, which showed -28ºC at 9,000 feet. Tara was asleep in the front with me, looking cold with her hat, scarf and mitts on. Anita, unusually for her, was awake in the back and gazing out of the window at the ground below. It was nearing dusk and stars were becoming visible in the crisp, Prairie sky.

By the time we passed Yorkton, it was fully dark outside. Suddenly I noticed something strange. The attitude indicator, which is a gauge that shows a miniature plane and its relation to an artificial horizon, had the little plane leaning as if in a left turn. I didn’t think I was turning. I looked outside to check. In the clear night, with the ground visible due to the snow and the towns twinkling brightly, I could see the horizon perfectly and saw that I was flying level. Obviously, the attitude indicator was malfunctioning.

To determine the cause of the problem, I made a rate one turn to the right for a few seconds followed by another to the left. The directional gyro was not responding either. This confirmed it: the vacuum pump had failed. A vacuum pump failure renders these two key navigation instruments useless. Thankfully, it does not in any way compromise the working of the engine.

I immediately informed the Winnipeg controller that I had suffered a vacuum pump failure, asking at the same time to be cleared down to 7,000 feet. He obliged. As I began my descent I thought, Why did I do that? She’s flying fine, the visibility, radio reception and gliding range are obviously better from higher up, and there are backup navigation instruments on board to help. I suppose, feeling vulnerable and rattled, I had instinctively wanted to be closer to the ground. Ah! That’s what my instructor had stressed in instrument ground school. He had warned us that in an emergency most pilots act instinctively and without thought, considering some action better than no action. On realizing a moment later the foolishness of reducing altitude, I requested a return to 9,000. The engine continued to do a fine job, immune to the navigation equipment failure.

As my heart rate returned to normal, I explained what had happened to Tara and asked her to help Anita retrieve my flight bag from the luggage hold behind her. I asked her to pull out the soap-holder suction cups that I had purchased for just such eventualities, as advised by IFR instructors. These fit nicely over the instrument gauges. I used them to cover up the attitude and direction indicators to prevent distraction by dysfunctional instruments. Center wanted to know our progress and whether any assistance was required. I informed them that all was fine now but that I would land earlier, in Brandon, Manitoba, about 100 miles west of Winnipeg.

A fire engine waited to greet us as we were pulling up to the terminal, a routine response in situations like ours. Luckily the plane didn’t need the fire engine, but we ourselves did because the airport by that time was totally deserted. We hitched a ride into town with it, the fire chief graciously taking us to the nearest hotel. After all this excitement we were glad to be able to go and relax in a hot tub, but not before I phoned in a report to Ulrike in Edmonton.

At 08:00 next day, New Year’s Eve, we arrived back at the Brandon terminal building with our fingers crossed. We knew it was highly unlikely an engineer would still be around on New Year’s Eve, and even more that he would be able to help with the vacuum pump. But, unbelievably, we had success on both fronts and would soon be able to continue the flight. I left Tara and Anita at the plane with the engineer and walked over to the briefing office to get the weather and to file a flight plan. Twenty minutes later, while I was in the midst of filling in the flight plan form, Anita ran up, agitated, and blurted out, “Papa, the engineer said to tell you that you’re not going anywhere today!”

We rushed back to the hangar where the engineer informed me, “You have a bent push-rod in one cylinder.” He had noticed it while changing the vacuum pump. A bent push-rod? This was serious and could lead to engine failure. Offhand he couldn’t offer any explanation as to the possible cause but seemed to feel that the roughness I’d experienced on leaving Edmonton may have something to do with it. Only an internal examination could confirm that. But why did the vacuum pump fail? Was there a connection or was it simply coincidence? No one knew. I could only thank my lucky stars, or Trevor’s horseshoe perhaps, that the vacuum pump failed when it did. It made me land earlier and possibly saved us from a real and potentially disastrous emergency.

I now arranged for the mechanics to fix the aircraft as soon as possible and then rushed out to see if we could fly commercially to Toronto. Luck was again on our side. There was a scheduled Canadian Pacific flight for Toronto right out of Brandon in three hours, and they had seats for us. While we didn’t arrive back in Toronto on December 30, as originally planned, we did make it back a half hour before midnight, New Year’s Eve, in time for a party with friends.

Six weeks later, the aircraft was ready. It turned out that one of the valves on a cylinder had become stuck, causing the push rod, which moves the valve up and down, to bend. Technically, there should have been very little or no power left on that cylinder. Since the plane has only four cylinders, the loss of one cylinder is a serious issue. Had I known one cylinder was not functioning, I definitely would not have departed from Edmonton. Yet I hadn’t felt any power loss, nothing except for that momentary roughness on takeoff, which shows how good those aircraft engines are (Lycoming, in my case). And as to the cause of the problem? Maybe the cold start in Regina? The engineers could not be sure; they said that this does happen on occasion.

Shortly after the repair was complete, I flew GVLD back to Toronto with two pilots, Gary, whom I had met in the lounge in Brandon and who offered to fly with me just for the fun of it, and Fausto Grazioli, an Italian banker and pilot friend. We departed for Thunder Bay with a weather forecast calling for ice fog with an outside air temperature of -28ºC for most of the journey except the last 50 miles. I’d never flown in ice fog before. Unlike in cloud, the temperatures in ice fog are so cold there is no chance of airframe icing occurring. When it’s that cold, sublimation via the wet or adhering state does not occur, so no ice forms on the aircraft surface.

I must admit I still felt tense and watched out for any signs of airframe ice, listening carefully as well to the sound of a newly repaired engine. I concentrated on the instruments, on keeping the aircraft straight and level and on the airway using only VORs, without an autopilot or GPS to help. After the three of us realized that all systems were fine, we were able to settle in and “enjoy” a true IFR flight in ice fog.

Flying in ice fog, I discovered, was like flying through thick white soup—endless white, zero visibility. You lose all sense of space, distance and motion. For all I knew, the plane could be standing still. Only the flight instruments and the muffled drone of the engine brought me back to reality. Flying like this minute after minute, hour after hour for nearly four hours was absolutely mesmerizing. The plane could begin flying sideways and in circles and I wouldn’t realize it if I didn’t stay focused on the instruments. Fortunately, I wasn’t alone in the plane which helped break any hypnotic spell.

Later, upon hearing my story, my IFR instructor, Barrie Aravandino, told me he thought that flying through ice fog for such a long stretch, particularly in a single-engine aircraft, was ill-advised. Looking back I probably agree and have never done so again.

A half-hour before Thunder Bay the sky started to open out, and we landed in VFR conditions, stopping there for the night. The rest of the flight to Toronto the next day was smooth and uneventful.

On landing at Buttonville I turned to GVLD, patted her on the nose and gave her a big kiss. I did this from then on after every flight, a thank you for bringing us home safely. Humbled after what we had been through, I realized that no matter how experienced I might become, in the end I still depended on my plane and all its essential parts.

The lesson for me was stark. One is never too prepared; the unexpected does happen. It is important not to overextend one’s risk appetite. And it is crucial to pay attention to and respond to every unusual event.

Shortly after the repair was complete, I flew GVLD back to Toronto with two pilots, Gary, whom I had met in the lounge in Brandon and who offered to fly with me just for the fun of it, and Fausto Grazioli, an Italian banker and pilot friend. We departed for Thunder Bay with a weather forecast calling for ice fog with an outside air temperature of -28ºC for most of the journey except the last 50 miles. I’d never flown in ice fog before. Unlike in cloud, the temperatures in ice fog are so cold there is no chance of airframe icing occurring. When it’s that cold, sublimation via the wet or adhering state does not occur, so no ice forms on the aircraft surface.

I must admit I still felt tense and watched out for any signs of airframe ice, listening carefully as well to the sound of a newly repaired engine. I concentrated on the instruments, on keeping the aircraft straight and level and on the airway using only VORs, without an autopilot or GPS to help. After the three of us realized that all systems were fine, we were able to settle in and “enjoy” a true IFR flight in ice fog.

Flying in ice fog, I discovered, was like flying through thick white soup—endless white, zero visibility. You lose all sense of space, distance and motion. For all I knew, the plane could be standing still. Only the flight instruments and the muffled drone of the engine brought me back to reality. Flying like this minute after minute, hour after hour for nearly four hours was absolutely mesmerizing. The plane could begin flying sideways and in circles and I wouldn’t realize it if I didn’t stay focused on the instruments. Fortunately, I wasn’t alone in the plane which helped break any hypnotic spell.

Later, upon hearing my story, my IFR instructor, Barrie Aravandino, told me he thought that flying through ice fog for such a long stretch, particularly in a single-engine aircraft, was ill-advised. Looking back I probably agree and have never done so again.

A half-hour before Thunder Bay the sky started to open out, and we landed in VFR conditions, stopping there for the night. The rest of the flight to Toronto the next day was smooth and uneventful.

On landing at Buttonville I turned to GVLD, patted her on the nose and gave her a big kiss. I did this from then on after every flight, a thank you for bringing us home safely. Humbled after what we had been through, I realized that no matter how experienced I might become, in the end I still depended on my plane and all its essential parts.

The lesson for me was stark. One is never too prepared; the unexpected does happen. It is important not to overextend one’s risk appetite. And it is crucial to pay attention to and respond to every unusual event.