We crisscrossed Canada several times over the span of a few years in C-GVLD. So, of the endless country airports in Canada, I’ve touched down on quite a few. One in particular, though not much different than the rest, is especially close to my heart - the one in Mayerthorpe, Alberta.

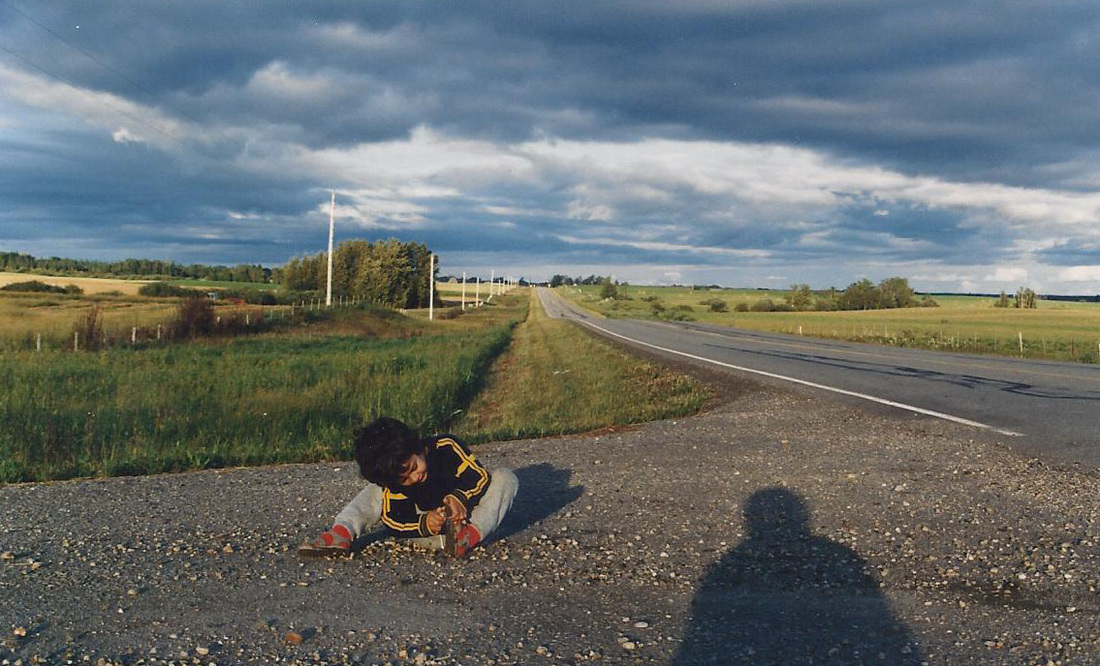

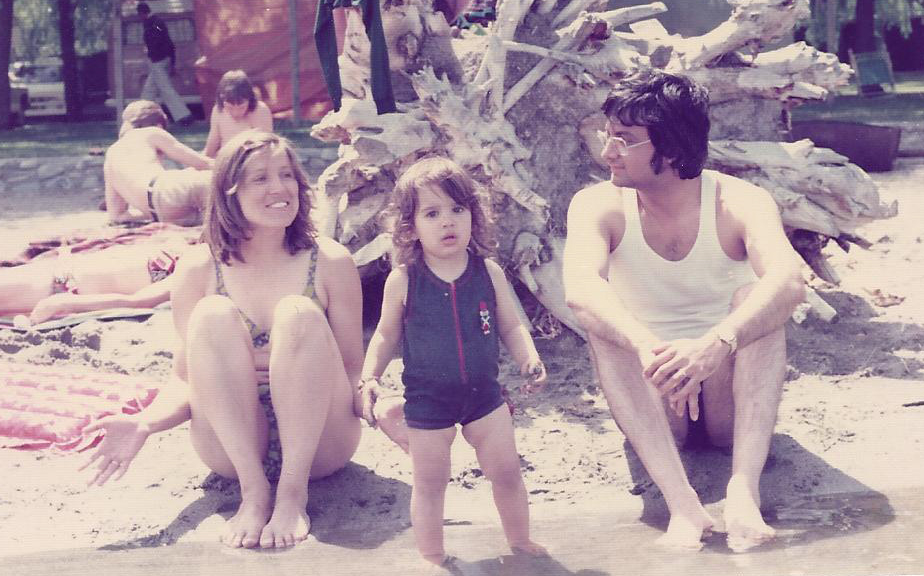

Mayerthorpe is a small town 60 miles northwest of Edmonton surrounded by rolling blue-green and sunflower-yellow fields, checkerboard roads, pastures dotted with black cattle, isolated farm houses, muskeg, coyotes, a few oil rigs, and the Conradi hobby farm, a three-quarter section of land bought by Ulrike’s parents in the 1970s. Any trip to Edmonton almost always included a visit to the farm.

Mayerthorpe is a small town 60 miles northwest of Edmonton surrounded by rolling blue-green and sunflower-yellow fields, checkerboard roads, pastures dotted with black cattle, isolated farm houses, muskeg, coyotes, a few oil rigs, and the Conradi hobby farm, a three-quarter section of land bought by Ulrike’s parents in the 1970s. Any trip to Edmonton almost always included a visit to the farm.

Why go there, people ask, to this spot in the middle of nowhere? A silly question for those who know and love the place and can easily rattle off a list of reasons. For me the farm at Mayerthorpe came to epitomize “getting away from it all.” In the late 1990s, during my time as chief executive officer of Standard Chartered Bank in Thailand, if I was having a bad day, my secretary Siriporn, a diminutive Thai lady, would sympathetically say, “I know, Khun (Mr.) Dru, you want to be in Mayerthorpe today. Let me bring you some good Oolong tea - it’s the next best thing to Mayerthorpe.” That pretty much says it all.

To get to the farm we’d drive with Ulrike’s mother Karin - “Mutti” to many of us - in her large Chrysler station wagon. It was packed with everything we would need for a few days’ stay: prepared meals, lots of wine and beer, steaks and cakes, and dark brown bread, the darkest baked by her. Sliced thinly and eaten with aged cheddar or Stilton, this bread was the best. We also brought copious amounts of water in large plastic containers because the well water, though drinkable, was murky light-brown in color and tasted swampy. Through the back window you could see a badminton racket or two poking out next to the game of Risk wedged between freshly laundered towels.

On the way we’d stop at Jack’s for ice cream cones or burgers. Jack’s wasn’t just a convenient pit stop on the way. It was a confection of its own, a small shack covered in chocolate-colored stucco, window frames a delicious yellow-orange. Ulrike’s father loved ice cream and was always the first to finish his cone, turning then “for a taste” to the slower eater next to him, who to salvage his cone ate faster and faster.

Finally, after driving one and a half hours, the last few miles along gravel roads, we were there. As we drove up the last stretch, a narrow lane, the house came into view. It was a lovely place with dormer windows and a broad wrap-around verandah. Grand views on all sides. Painted a pale sage green, it blended beautifully with the stands of poplars surrounding it. At the rear of the house, behind an electrified barbed-wire fence that separated a large lawn from meadows and fields, curious cows lined up to greet us. I often thought, gazing at that stretch of open land, that it would make a perfect landing strip.

After we parked, everyone quickly dispersed, the kids heading over to the old, abandoned two-story farm house just off to the side. It dated from the pre- electricity and running water era. A cast-iron wood stove still stood in the living room with its warped floor and crooked windows framed by dusty drapes. At the time the family bought the farm and this was the only house, petroleum lamps lit the way to the bunk beds in the one bedroom and to the iron bedsteads on the floor above. Mice now made their homes in the lumpy mattresses. A couple of trunks stashed here and there in dark corners still protected flotsam, papers, toys, old clothes and books. The kids loved this spooky, ramshackle place. It was their own.

With each passing year this original house leaned a little more precariously, the wood siding turned a deeper brown, smelled more richly of loam, and the moss on its roof extended its territory. Each year we wondered how much longer the house would remain standing. Next time we come, will it have collapsed and joined the stack of chopped-up poplars on the wood pile, ready for the fireplace and the cold nights of winter? When that time comes it won’t just be wood we’ll be burning, but memories.

The new, also two-storied, farmhouse stands just a little ways away from its crumbling sibling. Built in the early 1980s, it can, in a squeeze, accommodate up to twenty people. It has electricity, indoor plumbing and toilets – thankfully no more outhouse - marked improvements from the old place. There is still deliberately no TV and for many years there wasn’t even a phone. The outside world was disconnected; visitors when they came knew they were leaving a layer of life elsewhere. However, since the lack of a phone did cause mix-ups and problems, necessitating trips to the neighbor’s several miles away for urgent calls, that concession was eventually made. Otherwise the farm truly was a Shangri-La.

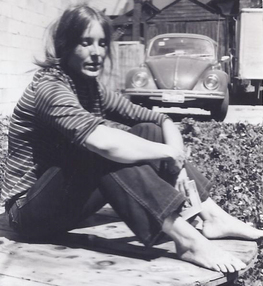

Immediately on arrival we’d stash our things in the bedrooms and help Mutti pack away the groceries. She would then make a quick check as to any damage done since the last time she was here, her bright blue eyes scanning her domain - are the roses still blooming, are the potatoes coming up, did those perennials survive the winter? Inside the house, if there was mouse dirt on the floors, she’d sweep that up. There rarely was much because she regularly went to the farm and tidied, repaired, and cleaned so that when the rest of us arrived it was inviting and cozy. A real labor of love.

After a quick meal we’d go for a long walk, over that barbed wire, across the fields, through cow pastures, avoiding still steaming cow patties, to a narrow winding little river. On hot days it was great for a swim and even better if you knew where the deep swimming holes were. The soft riverbanks were largely clay, which inspired dribbled sand castle contests and mud wrestling. The budding artists in the family, mostly 5 to 13 year olds, lugged large chunks of this clay, slippery and dripping back to the farmhouse. There, sitting in a circle on the lawn, they squeezed, pinched and molded it into various objects, mostly heads. Nixe, with her creative flair, would suggest a nose job here, a chin tuck there, until everyone was satisfied. If they survived the drying process, these heads, small, shriveled but expressive, would be put on display like so many hunting trophies on the living room fireplace mantle.

To get to the farm we’d drive with Ulrike’s mother Karin - “Mutti” to many of us - in her large Chrysler station wagon. It was packed with everything we would need for a few days’ stay: prepared meals, lots of wine and beer, steaks and cakes, and dark brown bread, the darkest baked by her. Sliced thinly and eaten with aged cheddar or Stilton, this bread was the best. We also brought copious amounts of water in large plastic containers because the well water, though drinkable, was murky light-brown in color and tasted swampy. Through the back window you could see a badminton racket or two poking out next to the game of Risk wedged between freshly laundered towels.

On the way we’d stop at Jack’s for ice cream cones or burgers. Jack’s wasn’t just a convenient pit stop on the way. It was a confection of its own, a small shack covered in chocolate-colored stucco, window frames a delicious yellow-orange. Ulrike’s father loved ice cream and was always the first to finish his cone, turning then “for a taste” to the slower eater next to him, who to salvage his cone ate faster and faster.

Finally, after driving one and a half hours, the last few miles along gravel roads, we were there. As we drove up the last stretch, a narrow lane, the house came into view. It was a lovely place with dormer windows and a broad wrap-around verandah. Grand views on all sides. Painted a pale sage green, it blended beautifully with the stands of poplars surrounding it. At the rear of the house, behind an electrified barbed-wire fence that separated a large lawn from meadows and fields, curious cows lined up to greet us. I often thought, gazing at that stretch of open land, that it would make a perfect landing strip.

After we parked, everyone quickly dispersed, the kids heading over to the old, abandoned two-story farm house just off to the side. It dated from the pre- electricity and running water era. A cast-iron wood stove still stood in the living room with its warped floor and crooked windows framed by dusty drapes. At the time the family bought the farm and this was the only house, petroleum lamps lit the way to the bunk beds in the one bedroom and to the iron bedsteads on the floor above. Mice now made their homes in the lumpy mattresses. A couple of trunks stashed here and there in dark corners still protected flotsam, papers, toys, old clothes and books. The kids loved this spooky, ramshackle place. It was their own.

With each passing year this original house leaned a little more precariously, the wood siding turned a deeper brown, smelled more richly of loam, and the moss on its roof extended its territory. Each year we wondered how much longer the house would remain standing. Next time we come, will it have collapsed and joined the stack of chopped-up poplars on the wood pile, ready for the fireplace and the cold nights of winter? When that time comes it won’t just be wood we’ll be burning, but memories.

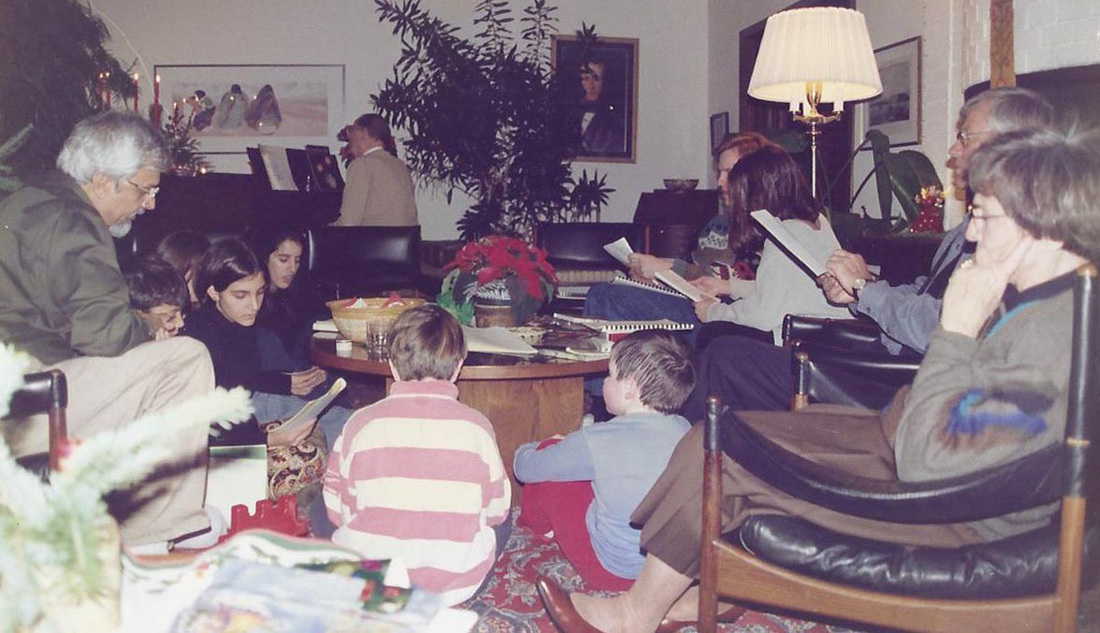

The new, also two-storied, farmhouse stands just a little ways away from its crumbling sibling. Built in the early 1980s, it can, in a squeeze, accommodate up to twenty people. It has electricity, indoor plumbing and toilets – thankfully no more outhouse - marked improvements from the old place. There is still deliberately no TV and for many years there wasn’t even a phone. The outside world was disconnected; visitors when they came knew they were leaving a layer of life elsewhere. However, since the lack of a phone did cause mix-ups and problems, necessitating trips to the neighbor’s several miles away for urgent calls, that concession was eventually made. Otherwise the farm truly was a Shangri-La.

Immediately on arrival we’d stash our things in the bedrooms and help Mutti pack away the groceries. She would then make a quick check as to any damage done since the last time she was here, her bright blue eyes scanning her domain - are the roses still blooming, are the potatoes coming up, did those perennials survive the winter? Inside the house, if there was mouse dirt on the floors, she’d sweep that up. There rarely was much because she regularly went to the farm and tidied, repaired, and cleaned so that when the rest of us arrived it was inviting and cozy. A real labor of love.

After a quick meal we’d go for a long walk, over that barbed wire, across the fields, through cow pastures, avoiding still steaming cow patties, to a narrow winding little river. On hot days it was great for a swim and even better if you knew where the deep swimming holes were. The soft riverbanks were largely clay, which inspired dribbled sand castle contests and mud wrestling. The budding artists in the family, mostly 5 to 13 year olds, lugged large chunks of this clay, slippery and dripping back to the farmhouse. There, sitting in a circle on the lawn, they squeezed, pinched and molded it into various objects, mostly heads. Nixe, with her creative flair, would suggest a nose job here, a chin tuck there, until everyone was satisfied. If they survived the drying process, these heads, small, shriveled but expressive, would be put on display like so many hunting trophies on the living room fireplace mantle.

On summer evenings, a short distance from the house, Julian with cousins Ben and Stephanie, launched massive fires in the fire pit, a rectangle bordered by thick logs reaching 20 feet in length, whose proportions, they figured, justified fires ten feet high. As the air cooled and the sun went down in brilliant reds we all gravitated to the warmth and crackling of the flames and barbecued wieners and marshmallows. The delicious smells of slightly burned meat and melting sugar made a lager or a glass of Gewuerztraminer irresistible.

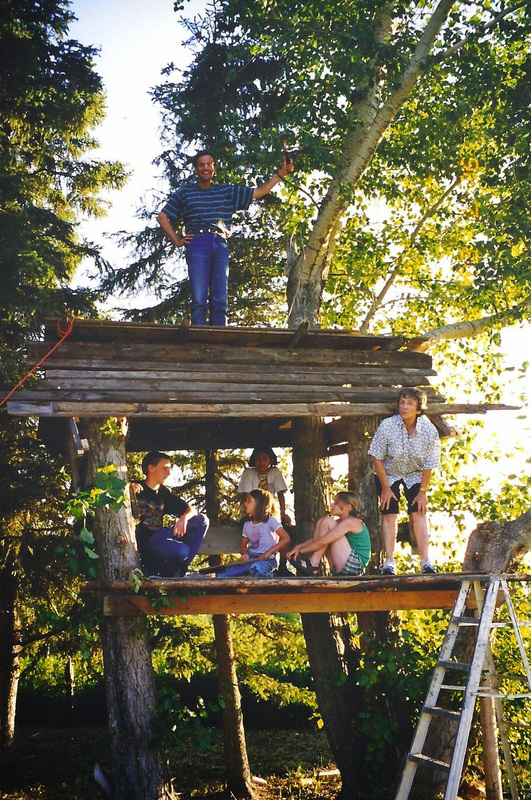

Camp memories stirred. Someone burst out with the familiar bouncy tune “She’ll be coming around the mountain when she comes.... She’ll be wearing pink pajamas when she comes.... She’ll be riding six white horses when she comes....” For once, the coyotes in the dark woods on the horizon were rendered silent. Then, after a deep breath, we all slid into the Beatles’ “Hey, Jude.” Other songs followed, me providing that low background hum. As the evening deepened and people became silhouettes, there was always someone who, having swallowed inhibition with his beer, growled out a curdling rendition of Louis Armstrong’s “Mack the Knife” or, if the singer was German, “Makki Messer.” With a bright moon in the sky, the beautiful old German family favorite “Der Mond ist aufgegangen” (“The moon has risen”) would inevitably be sung and when the fire was dying down and our eyes glazed over, the canon “Oh wie wohl ist mir am Abend” (“Oh how great I feel in the evening”) made our beds seem an enticing breath away. The kids didn’t have far to go, climbing up into the roomy tree house right next to the fire pit, a penthouse with view that they had helped build.

I loved the farm especially in winter. Alberta’s ample, crunchy dry snow converted the area into a cross-country skiing heaven, with trails leading down to and along the endlessly looping frozen river and a clear sun shining all day in a bright blue sky. But I gladly left that to others. I, instead, sat on the verandah dressed in a thick parka, a good book in my hand, maybe a tea, and enjoyed the utter quiet, the sparkling snow, and that wonderful nip in the air.

For all these reasons the farm had a soft spot in my heart, and I knew that there would come a day I would fly there in the Cessna. In the summer of 1989 I stamped that flight into our plans, an add-on to a flight from Toronto to Edmonton.

For all these reasons the farm had a soft spot in my heart, and I knew that there would come a day I would fly there in the Cessna. In the summer of 1989 I stamped that flight into our plans, an add-on to a flight from Toronto to Edmonton.

When flying over such a huge stretch of country - just under 2,000 miles - you expect to encounter all kinds of weather, especially in summer. What we weren’t prepared for was massive forest fires. Actually we shouldn’t have been surprised. Fires that destroy thousands of acres of forest are not uncommon in dry hot summers. Approaching the Lake of the Woods area of Manitoba, we saw to our amazement what looked like Dante’s inferno, a fire so intense, so extensive its towering, billowing clouds of smoke blackened the sky from horizon to horizon.

I knew those clouds could be as dangerous as CBs, cumulonimbus clouds that build during thunderstorms. Such clouds can go extremely high and with hurricane-force winds churning up and down within them they can easily tear a small plane apart. Nope, we weren’t going anywhere near there. I made a quick 90-degree turn and headed south about 50 miles to the U.S., skimming along the border until we were safely beyond that conflagration. The rest of the flight, except for a squall here and there, was uneventful.

A few days after landing in Edmonton, it was off to Mayerthorpe. Though very tempting, I had decided against landing on the meadow behind the farm as it had potentially dangerous bumps and holes. Landing there would also set the cows stampeding making them lose precious pounds to the great displeasure of their owners. Fortunately, Mayerthorpe had an actual airport situated just across the main highway from the town. It was uncontrolled and little more than a good-sized asphalt strip. But that would be more than sufficient.

Ulrike’s nephew Jens was going to join me. He’d never flown in a Cessna before. On the day of the flight the weather briefing called for a fair weather day, sunshine but with moderate thermals that typically build in the afternoon causing mildly bumpy conditions. Though not ideal conditions for a first flight, I figured it wouldn’t be too bad and the flight was short, just two-thirds of an hour. At the coffee shop in the airport terminal I suggested to Jens that if he had not eaten, he might wish to grab a bite but not to overeat in case the flight proved to be bumpier than envisaged. While I filed the flight plan, Jens, a six-foot, hungry young man, used the moment to have some fries and a coke, wolfing down the last of the meal when he saw me returning. We headed off to the plane.

As soon as we were strapped into our seats ready for takeoff, I briefed Jens about the controls and panel gauges and instruments, offering to let him handle the controls once we had departed. Except for the expected thermal activity, it was a wonderful flying day. Jens got a feeling of the controls en route, really excited as he realized that controlling the aircraft in flight was not all that difficult and in fact quite a pleasant experience. He kept asking questions about how long it would take to get a license, the cost of it, and on and on. I might have a convert on my hands I thought to myself, feeling quite elated at that prospect. He might in turn help kindle interest in our three children, who were quite a few years younger.

As we got close to the airstrip at Mayerthorpe I decided to do a couple of low, slow passes over the farmhouse to announce our arrival to those who were already there, hoping for a car pickup. As we approached, rocking our wings and waving, more than a dozen family members gathered on the lawn at the rear of the house and cheerfully waved back. Then I climbed back up again and continued on for a landing at the Mayerthorpe municipal airstrip.

I knew those clouds could be as dangerous as CBs, cumulonimbus clouds that build during thunderstorms. Such clouds can go extremely high and with hurricane-force winds churning up and down within them they can easily tear a small plane apart. Nope, we weren’t going anywhere near there. I made a quick 90-degree turn and headed south about 50 miles to the U.S., skimming along the border until we were safely beyond that conflagration. The rest of the flight, except for a squall here and there, was uneventful.

A few days after landing in Edmonton, it was off to Mayerthorpe. Though very tempting, I had decided against landing on the meadow behind the farm as it had potentially dangerous bumps and holes. Landing there would also set the cows stampeding making them lose precious pounds to the great displeasure of their owners. Fortunately, Mayerthorpe had an actual airport situated just across the main highway from the town. It was uncontrolled and little more than a good-sized asphalt strip. But that would be more than sufficient.

Ulrike’s nephew Jens was going to join me. He’d never flown in a Cessna before. On the day of the flight the weather briefing called for a fair weather day, sunshine but with moderate thermals that typically build in the afternoon causing mildly bumpy conditions. Though not ideal conditions for a first flight, I figured it wouldn’t be too bad and the flight was short, just two-thirds of an hour. At the coffee shop in the airport terminal I suggested to Jens that if he had not eaten, he might wish to grab a bite but not to overeat in case the flight proved to be bumpier than envisaged. While I filed the flight plan, Jens, a six-foot, hungry young man, used the moment to have some fries and a coke, wolfing down the last of the meal when he saw me returning. We headed off to the plane.

As soon as we were strapped into our seats ready for takeoff, I briefed Jens about the controls and panel gauges and instruments, offering to let him handle the controls once we had departed. Except for the expected thermal activity, it was a wonderful flying day. Jens got a feeling of the controls en route, really excited as he realized that controlling the aircraft in flight was not all that difficult and in fact quite a pleasant experience. He kept asking questions about how long it would take to get a license, the cost of it, and on and on. I might have a convert on my hands I thought to myself, feeling quite elated at that prospect. He might in turn help kindle interest in our three children, who were quite a few years younger.

As we got close to the airstrip at Mayerthorpe I decided to do a couple of low, slow passes over the farmhouse to announce our arrival to those who were already there, hoping for a car pickup. As we approached, rocking our wings and waving, more than a dozen family members gathered on the lawn at the rear of the house and cheerfully waved back. Then I climbed back up again and continued on for a landing at the Mayerthorpe municipal airstrip.

On the base leg, unexpectedly, I saw Jens opening his side window. I figured he probably needed some fresh air. It was a hot day and in slow flight just before touchdown the air vents become rather ineffective. I glanced over again to ensure he was all right. He looked fine. The very next moment, however, he stuck his head outside and heaved - the wrong maneuver, unfortunately, because the wind blew virtually everything back inside. Most of Jens’s recent meal landed on the back seat and the baggage area. As luck would have it, only the airsickness bags in the pockets behind our seats were spared.

Moments later I touched down and taxied over to what looked like a shack, but was actually the terminal building. No one was inside. Sparse furnishings included a folding table and a few folding chairs. Fortuitously there was also an ancient kettle on a counter, and, yes, a washroom. We filled the kettle with water and managed to give the plane a cursory cleaning. A pay phone on the outside wall allowed us to call the farmhouse to ensure we would get a pickup ride. We decided to return later with better equipment, mops, detergent, brushes and towels. Jens, though, insisted on returning alone and in the end cleaned and restored the plane to a better condition than before. Six months later, while getting the rugs professionally cleaned, what did I find behind the baggage wall? A sole French-fry, fully intact.

As we waited for the car, I glanced around at the airstrip, at our lone airplane tied down outside the hut. There was not a soul in sight, not a sound. Nothing but prairie peace and tranquility and gently rolling farmland as far as the eye could see. This was the Mayerthorpe I would frequently come to yearn for later during my frantically paced years of work. Here it was in its fullness, a wide-open no fuss no muss environment, where there was time for family and friends, and a quiet corner for myself. I felt immensely grateful. A few days later I rose up again into the prairie sky to return to Edmonton. As I climbed higher and higher, the farm, the fields and roads, the whole solid world beneath me shrank and the sky expanded until I was drenched in blue, nothing but blue, brilliant, clear and endless.

Moments later I touched down and taxied over to what looked like a shack, but was actually the terminal building. No one was inside. Sparse furnishings included a folding table and a few folding chairs. Fortuitously there was also an ancient kettle on a counter, and, yes, a washroom. We filled the kettle with water and managed to give the plane a cursory cleaning. A pay phone on the outside wall allowed us to call the farmhouse to ensure we would get a pickup ride. We decided to return later with better equipment, mops, detergent, brushes and towels. Jens, though, insisted on returning alone and in the end cleaned and restored the plane to a better condition than before. Six months later, while getting the rugs professionally cleaned, what did I find behind the baggage wall? A sole French-fry, fully intact.

As we waited for the car, I glanced around at the airstrip, at our lone airplane tied down outside the hut. There was not a soul in sight, not a sound. Nothing but prairie peace and tranquility and gently rolling farmland as far as the eye could see. This was the Mayerthorpe I would frequently come to yearn for later during my frantically paced years of work. Here it was in its fullness, a wide-open no fuss no muss environment, where there was time for family and friends, and a quiet corner for myself. I felt immensely grateful. A few days later I rose up again into the prairie sky to return to Edmonton. As I climbed higher and higher, the farm, the fields and roads, the whole solid world beneath me shrank and the sky expanded until I was drenched in blue, nothing but blue, brilliant, clear and endless.