***

Who hasn’t yearned for adventure? Who hasn’t paused for a moment while reading the morning paper - a faraway look in their eyes? Or driving home some evening, mind in neutral, who hasn’t suddenly felt that magnetic pull to somewhere else, the next town, the next country, around the globe? Wondered how it could be done? Dreamed, made plans, but then turned back? Because there’s never any room for that. Because the everyday with its comfortable routines and pressing needs squeezes out exotic visions. Because it’s all too complicated.

Sometimes, however, life can be a rooster at four a.m., waking you with a sudden call - insistent, irresistible - that changes life forever.

For me there was no turning back. It was that call that got me out of bed on this particularly dark and freezing December morning in Toronto in 1977. My alarm had just gone off at an unbearably early 5 a.m. I glanced over at Ulrike, snug as a bug. As much as I might have wished, it was too late to cancel my flying lesson an hour and a half before the scheduled time.

I couldn’t schedule lessons at any other time of day because of work. I had to be downtown on Bay Street by nine at the latest and couldn’t guarantee getting away by a particular time in the evening. To be honest, the early mornings weren’t so bad. The lessons were only once a week and I knew that as soon as I was out of bed and on my way, I’d be looking forward to it all.

Dressed and slightly more awake, I phoned the aviation flight service station (FSS) for a weather briefing. A cheery voice announced, “As long as you don’t mind using the scraper on the car windshield to begin with, the rest of the morning should be just fine.”

The moment I stepped outside I realized how cold it really was and pulled my parka hood firmly over my head. As forewarned, I did have to scrape the frost off the windshield before I could even think about backing the car out of the carport. It was a grim reminder of what might be facing me at the airport. I prayed someone had had the forethought the night before to park the school aircraft inside the hangar. If not, I knew it would take at least half an hour to get the frost off the wings and other surface areas of the Cessna. My warm bed suddenly seemed very inviting indeed. Was this really worth it?

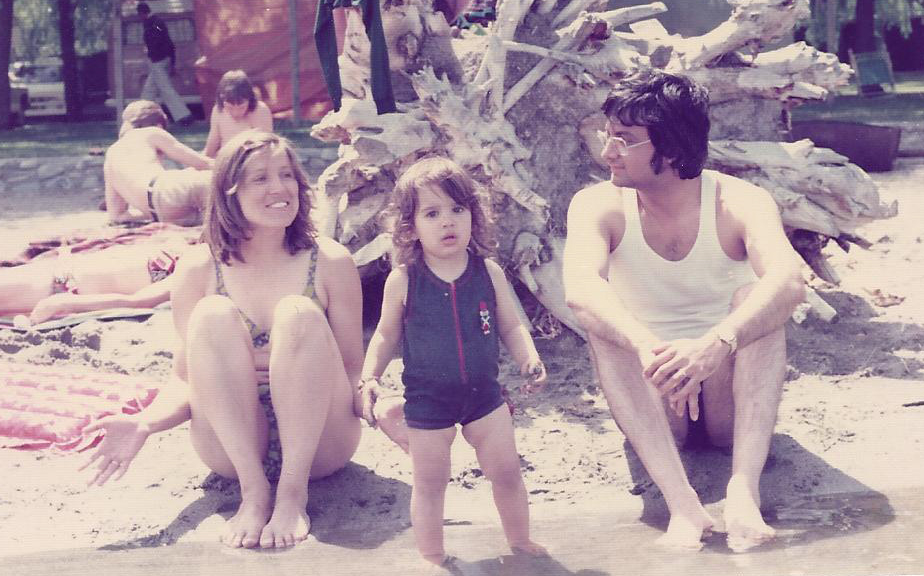

There was also the cost. Flying was expensive, at least for our young family: $55 dollars per hour for the aircraft rental and the instructor’s time. One class a week added up to $3,000 for the year, a sizeable chunk out of a disposable income of $16,000. The mortgage for our very modest suburban brick bungalow was small, but because of high interest rates, the payments were significant. Our car, Ulrike’s aging red Volkswagen Beetle, a high school graduation gift from her parents, would also have to last a few more years. I had a small pang of conscience as I tried to start the frozen car.

Luckily, Ulrike never complained - at least out loud. She, too, was excited at the prospect of flying in the skies one day. As I scraped the windshield in the dark, I wondered what her day would be like at home with Tara, our four-year-old, and my ailing mother. Unlike me, Ulrike was a naturally early riser and would soon be getting up.

Once I was behind the wheel, all qualms vanished. With the heater on full blast, I drove north along Kennedy Road, towards Highway 401, stopping briefly at my usual, Dunkin’ Donuts, to grab a coffee and Danish. Cruising along the highway toward Buttonville Airport on the northern edge of the city, I broke into a smile. Everything was perfect. The morning was crisp and clear, the radio was tuned to my favorite FM station, the traffic was light, the coffee wonderful, and I was driving to the most prized destination I could imagine.

Soon I would be up in the air heading over Toronto’s still dark streets towards its skyline glittering in pre-dawn light, towards the needle of the CN tower, the emphatic pale pink marker for a right turn. Then I’d be skimming along the frozen shore of Lake Ontario as the night sky brightened, the stars dimmed, and the sun slid over the horizon to begin a new day. There would be barely any air traffic to worry about at that hour, at least as far as light planes were concerned. And in those days, instructors kept us far away from the heavy jet traffic at Toronto’s Pearson International. As always, thinking about my flight sent joyful shivers up my spine.

When I drove into the airport parking lot, there was no one at the ticket booth yet and hardly any cars around. It was difficult to believe this was one of the ten busiest small airports in Canada. Inside the terminal building, I walked through the coffee shop, the chairs still turned upside down on the tables from the previous night’s mopping. The only sign of life was the flight school dispatcher Dave, behind the counter. He greeted me, simultaneously flicking the security door switch underneath the counter to let me out into the secure airport apron area. I walked through with my flight briefcase, once again fully zipped up in my parka, gloves donned, winter boots buckled, ready for round one.

Thirty-five minutes later, I had done the pre-flight walk around the aircraft using my flashlight, brushed and scraped the frost off all the surfaces, started the engine and pulled up to the gas pumps. Ten minutes later, with both high-wing tanks filled up, I taxied back to the terminal building to pick up my flight instructor, Bal Suagh. The aircraft cabin was now toasty, it was precisely two minutes to seven, and I was still smiling as he climbed into the aircraft with a friendly, "Good morning."

As the propeller cut speech short and drowned out our conversation for a moment, exhilaration surged. Both the plane and my spirit rotated upwards and lifted into that open-ended, God-only-knows-where-it-might-take-me wonderful space.

Sometimes I still couldn’t believe it. Here I was, at the age of twenty nine, learning to fly. As a young boy, I’d often watched planes flying around airfields near Calcutta, the city of my birth. During my second year of university in Calcutta, I even applied to the Air Force in my eagerness to become a pilot, but was turned down because I needed eyeglasses. Disappointed, I applied to and was accepted by the Officer’s Training School of the Army—definitely a wrong turn. I couldn’t accept that I, a novice officer-in-training, would one day have to give orders to older and more experienced men simply because they had not had the benefit of a university education. Very early morning wake-up calls furthered my disgust. So did climbs up forty-five-degree hills with a heavy backpack at temperatures high enough to wilt a cactus. No, the army was definitely not for me. I backed out at considerable financial loss to my family. Flying now disappeared from my radar as I turned to other possibilities.

After graduating with a Bachelor of Commerce in 1969, I knew that the logical next step would be to apply for an entry-level management position at major corporations. But I wasn’t ready for that. A world was out there to explore. I had to go.

My father, on hearing of my decision to leave India, complained, “Beta (son), that’s irresponsible.” I could understand that coming from my father. He had had an arranged marriage at thirteen, had been the only member of his family to finish high school, had fled Pakistan to India with a wife and two children at the time of partition in 1947 and had, through initiative and many years of hard work, become a wealthy businessman. As the owner of the well-known Cambridge bookstores in Calcutta and Darjeeling he had supported not only his own family, but also the families of his four younger siblings. Clearly he knew where my priorities should lie.

My mother appealed to me:

“Papou (a nickname that has stayed with me), don’t go. There is a good future for you here. What is there to see in the world?”

My friends all thought about joining me:

“Areh, Papou, love to go, too, but, you know, I already have a job.”

“My three sisters, have to get them married. You know how it is. So sorry.”

“Responsibilities. My elderly parents. I’m comfortable here. But do go on. Keep in touch.”

My friend Khokon Guha was the only one eager to come along. Our plans were simple: to go to America. Traveling on an old cargo ship, a dhow, we headed first across the Arabian Sea to the port of Khoramshar in Iran. We camped on deck beside a group of hippies to avoid the ship’s stifling hold which was filled with cargo and with workers and whole families on their way to work in the Middle East. Their hammocks were strung up in every available space. After a brief stay in Tehran we hitchhiked to Europe through Turkey, Greece and Yugoslavia.

With only $15 (USD) in our pockets - all we were permitted to take out of India at the time - we were in definite need of additional income. In Greece, we donated blood. In Yugoslavia, in the small malls of various towns, we sold jewelry and trinkets we had brought along from India. The local women, for whom these items were novel and beautiful, crowded around us, outbidding each other. We didn’t understand a word, but everyone left satisfied. Stuck at the Austrian/Yugoslavian border without a ride, we spent a quite comfortable night in a jail cell courtesy of the Austrian border guard; it was a good thing that the night shift left a note regarding us for the morning shift! Finally, in Stuttgart, Germany, we earned enough at a car parts factory to purchase airline tickets to North America.

We arrived in Toronto in May 1970. When I went through immigration as a visitor at the Toronto International Airport, I had exactly $10.60 (CAD) in my pocket. The immigration officer naturally wanted to know how much more money I would be sent later from overseas. When I answered that that was all I had to my name, he looked incredulous. Of course, he then became more interested in knowing how I was going to support myself. Luckily, Khokon’s uncle in Toronto had offered to provide for us financially. A few months later we applied for and received our immigration papers, and three years after that, our Canadian citizenship.

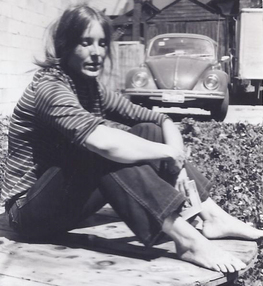

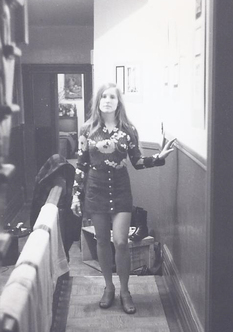

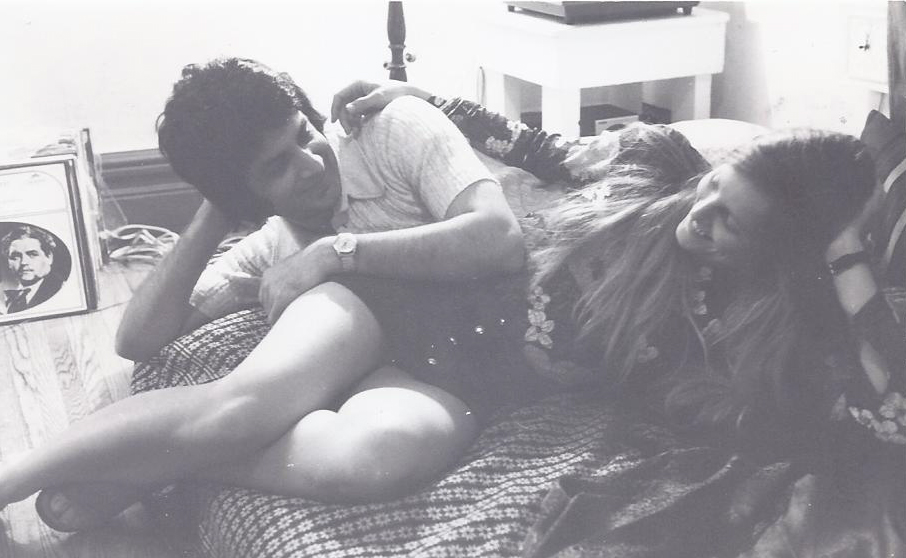

| In 1970 I also met Ulrike. We were both renting rooms in a student rooming house on the University of Toronto campus. I recall the day she moved in, on the floor above me. My new friend, George Sawa, a tall Egyptian with a huge halo of brown curly hair, said to me, “Narwani, you have to see this beauty who just moved in upstairs.” Naturally I agreed. I sauntered upstairs pretending to call on Lucy, who I knew had a crush on me. In the narrow hallway upstairs, at a little coffee table, sat this girl dressed in a green army shirt and tight blue jeans, holding a book in her hand. She had hazel-green eyes, an hourglass figure, and blonde hair down to her waist. (I also had long hair at the time, down to my shoulders. It was the Age of Aquarius and Hair, after all.) To top it all off, what a wonderful smile she had! She looked so young I guessed she’d just entered her undergraduate program. Weeks later, after we had dated a few times, I discovered that she was enrolled in a PhD program in Slavic languages and Russian literature. By then, I had started an evening program for a degree in management accounting, and was working during the day as an accounting clerk. All this time, flying was nowhere on the horizon. |

We married in 1972 and by 1977 both of us had graduated. I was by then in a middle-management position at the head office of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. Ulrike was busy with Tara. We had little money and so were fortunate our talkative little “jabberwocky” was easily satisfied. She loved to play with onions on the kitchen floor, wear tights on her head, and collect leaves in the fall, stuffing them into her closet "to protect them from winter." Ulrike was also learning “kitchen” Hindi to communicate with my mother, who had come to live with us and barely spoke two words of English. Who would have thought at the time that this Hindi would stand Ulrike in good stead in later years?

Then the fates intervened. One morning in the fall of 1977, while reading the newspaper on the subway on my way to the office, I read a section about flying schools in the Toronto area. As the train passed station after station, the car gradually filling with people, an old dream resurfaced. My studies were behind me, and I had more disposable income - I could now learn to fly.

Never one to wait when I wanted something, I phoned as soon as I got into the office and made a booking for a half-hour familiarization flight at the suburban airport of Markham. With that spontaneous action, flying entered my life. At the time I could not have imagined its impact on all our lives and the incredible adventures it would lead to over the next twenty-five years.

***